Run a command within a container

Containers are related to virtual machines, but aren’t the same thing. The main difference between a container and a virtual machine is that a container does not contain or run an entire operating system. Instead, containers run within an existing operating system. The theory is that a container uses fewer resources because it doesn’t carry all the extra baggage of a complete operating system.

One fairly common use of containers is to distribute complex software and its dependencies as a single “image”, similar to what you downloaded for SerenityOS when you were setting up a virtual machine. An image is basically an archive of an operating system’s folder structure.

We could spend an entire course talking about the technical foundations of containers (that would be an amazing systems course), but in this course our goal is simple: install enough software to get a command running in a container.

Install Docker Desktop

Undoubtedly the most popular container management software is Docker.

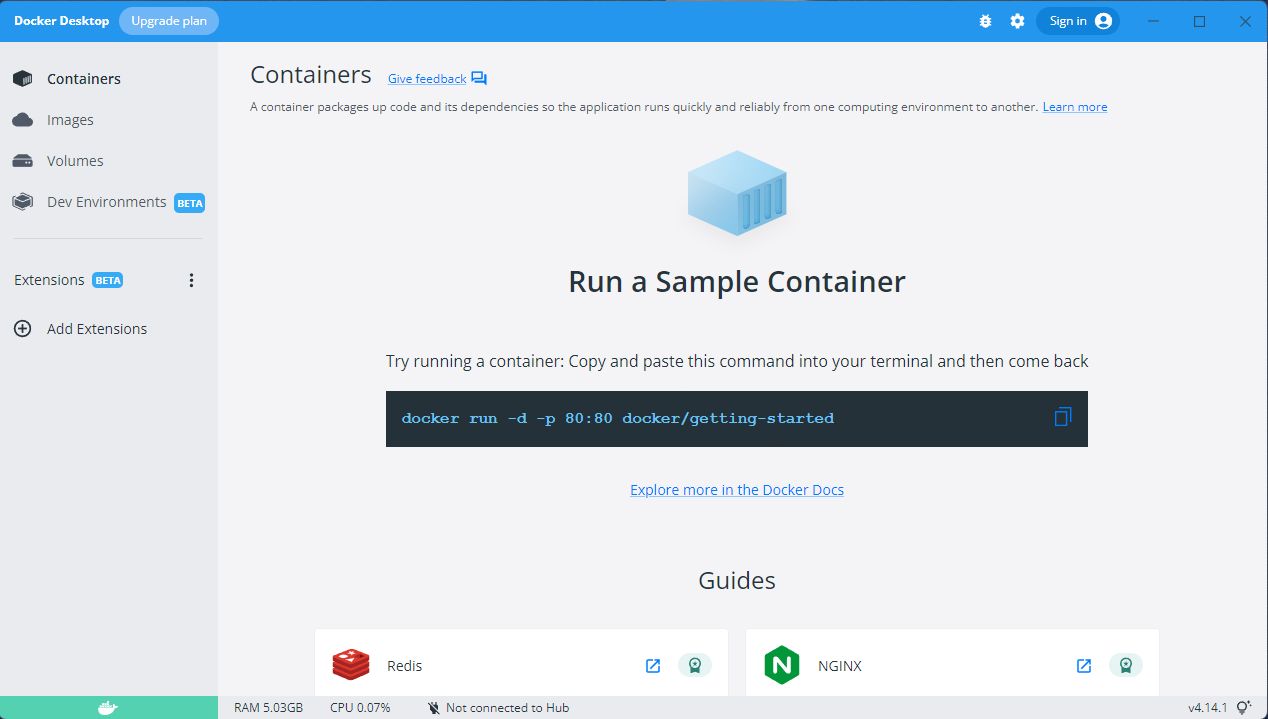

Docker has a highly polished visual environment for managing containers called Docker Desktop.

You should install Docker Desktop on your personal computer, following the instructions provided in Docker’s documentation.

If you’re installing Docker Desktop on Windows, you’re going to need to install the Windows Subsystem for Linux. There’s a link in Docker’s documentation, but for completeness, you can find documentation about how to install WSL on Microsoft’s web site.

Run a command within a container

The simplest container command to run is “hello world”, so let’s start with that, then move on to something a little more complex.

Let’s start by running the Docker Desktop app on your computer. This step isn’t required (you don’t need to start Docker Desktop before running any commands), but gives us an idea of the kinds of things we can do with Docker Desktop.

We’re not going to do anything with Docker Desktop, but note the tabs on the left:

- Containers: This is a list of running containers that you can inspect and interact with.

- Images: These are the container images that have been downloaded for launching containers on your machine.

- Volumes: Containers can’t see or interact with the files on your computer at all (they’re completely self-contained). Volumes are a way for you to share folders from your computer to a container so that you can either provide inputs or receive outputs from a container.

Let’s run a hello world container. If you had a terminal open before,

close your terminal and re-open it; your PATH variable

(yes, there is a PATH on all of Windows, macOS, and Linux)

was modified by Docker Desktop when you installed it.

Once your terminal is open again, run the following:

docker run hello-worldYou should see some output from Docker:

docker run hello-worldUnable to find image 'hello-world:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/hello-world

2db29710123e: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:faa03e786c97f07ef34423fccceeec2398ec8a5759259f94d99078f264e9d7af

Status: Downloaded newer image for hello-world:latest

Hello from Docker!

This message shows that your installation appears to be working correctly.

To generate this message, Docker took the following steps:

1. The Docker client contacted the Docker daemon.

2. The Docker daemon pulled the "hello-world" image from the Docker Hub.

(amd64)

3. The Docker daemon created a new container from that image which runs the

executable that produces the output you are currently reading.

4. The Docker daemon streamed that output to the Docker client, which sent it

to your terminal.

To try something more ambitious, you can run an Ubuntu container with:

$ docker run -it ubuntu bash

Share images, automate workflows, and more with a free Docker ID:

https://hub.docker.com/

For more examples and ideas, visit:

https://docs.docker.com/get-started/🎉 you just started and ran a container on your computer!

When you go back to Docker Desktop, you’ll be able to see that in the

Containers tab is a container with the image

hello-world:latest that has “Exited”. This is the container

you just ran.

You can technically run it again by pressing the play button ▶️ on the right side of

the window, but it’s not going to do anything because the

hello-world image prints to standard output, and there is

no standard output display in Docker Desktop.

You can (and probably should) delete this container by clicking on the trash can 🗑️ icon on the far right side of the window.

Hello world is always our classic “let’s try this out for the first time” exercise, and while interesting, isn’t really giving us a good idea of the kinds of things we can do with containers — we were already able to write our own self-contained “Hello world” programs in Java, C, or Python (or whatever). Let’s step up to something a little bit more complicated.

Let’s follow the advice of Docker Desktop and “Run a Sample Container”. Run the following in your terminal:

docker run -d -p 80:80 docker/getting-startedDocker does some stuff to download an image and then… nothing?

Let’s step through what each of these options mean:

runis… well, it means download the image and run a new container using that image as a basis. We saw that happening,dockerprints out a bunch of fancy animations showing progress downloading images.-dis “detach”. This means that Docker is going to start the container, and then run it “in the background” (the container will still be running, but you can continue to use your terminal).-pis “port forwarding”. This is getting pretty far outside the scope of our course, but one way to interact with applications is through a “port”. Port 80 is the port for HTTP, and HTTP is the “protocol” (sort of like the language) that your web browser (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge) use to talk to web servers. This is a bit of a hint about how to start interacting with this container.docker/getting-startedis the name of the image that we want this container to use when it launches.

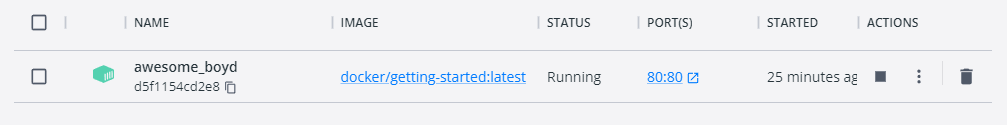

You can check in Docker Desktop and see that this container is indeed running:

Notice that you can click on the entry in the “Port(s)” column for this container. Click on it!

Hey! Look at that! You’re running a web server in this container, and your web browser is interacting with the web server in the container. 🎉

This web server actually contains extensive documentation for using Docker, so if you’re looking for some further reading about Docker, this is one place you can find it.

Running a web server in a container is an example of a long-running

application. Let’s do something that’s a little bit different: we’re

going to run pandoc in a container.

… pandoc? That feels a little underwhelming.

OK, well, sure, it’s familiar, but we’re going to be doing

things in a container that has a bunch of stuff configured that you

can’t do with the base pandoc install, including being able

to produce PDFs on your Windows or macOS machine without installing

\LaTeX.

We’re going to use pandocker. Let’s write

ourselves a little Markdown file that takes advantage of some features

in pandocker that we

can’t do with the base pandoc install:

https://code.cs.umanitoba.ca/cs-lab-course/hello-pandocker/-/raw/main/hello-pandocker.mdYou should use this file to:

Create a PDF on Aviary with

pandocpandoc myfile.md -o myfile.pdf --tocThen transfer the PDF back to your own computer so you can see what it looks like.

Create a PDF on your own machine with Pandocker using the following command:

macOS or Linux

docker run --rm -v `pwd`:/pandoc dalibo/pandocker:stable \ $YOUR_FILE.md -o $YOUR_FILE.pdf --filter pandoc-latex-admonition \ --template eisvogel --toc --pdf-engine=xelatex --listingsmacOS with Apple Silicon

docker run --platform=linux/amd64 --rm -v `pwd`:/pandoc \ dalibo/pandocker:stable $YOUR_FILE.md -o $YOUR_FILE.pdf \ --filter pandoc-latex-admonition --template eisvogel --toc \ --pdf-engine=xelatex --listingsWindows with PowerShell

docker run --rm -v ${PWD}:/pandoc dalibo/pandocker:stable lecture.md -o ` lecture.pdf --filter pandoc-latex-admonition --template eisvogel --toc ` --pdf-engine=xelatex --listings

These two outputs are pretty different! As it is, you can’t generate the same output on Aviary as you could with Docker and pandocker on your own machine — configuring Pandoc with all of the required filters, templates, and supporting software is tedious and painful.

There are a lot of options in this, but most of them are actually

options for pandoc and not Docker. Let’s step through the

Docker options:

--rm: This option tells docker to remove the container after it exits. This is a short-running container, so removing it once it’s exited makes sense.-v (pwd):/pandoc: This is how we share files with a container. The-voption is to “bind mount a volume”. The short of this is that inside the container is another directory structure, andpwd(your present working directory) is shared inside the container at/pandoc.

That’s it for Docker options! The rest are options to

pandoc that you can read about in the documentation for

pandoc.

🎉 You just ran

pandoc in a container!

Further reading

You’ve seen two examples of how to use containers, but you might want to know more about how to create your own containers.

- Read more about creating containers in Docker’s Get Started, either on Docker’s web site or in the getting started container you launched earlier. This will take you further into containers and get you creating your own containers.

- Docker isn’t the only tool for managing containers, Podman is an alternative tool for managing containers.

- If you’re looking for a deep dive alternative, FreeBSD Jails predate the idea of containers.